Boston's North End, an Italian-American neighborhood for a hundred

years, has an attractive new book store, I AM. The store hosted a program that included long-suppressed

film footage of the Sacco-Vanzetti funeral march, a reading from the

published letters of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, and my

presentation on "Suosso's Lane."

Boston's North End, an Italian-American neighborhood for a hundred

years, has an attractive new book store, I AM. The store hosted a program that included long-suppressed

film footage of the Sacco-Vanzetti funeral march, a reading from the

published letters of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, and my

presentation on "Suosso's Lane."The movie newsreel film footage, taken of the Aug. 27, 1927 funeral march following the unjust executions of the two Italian immigrants, was suppressed by the American government, which told movie distributors to destroy the prints. The funeral march drew an estimated 200,000 people, the largest public gathering in Boston until recent times. The government sought to discourage all future attention to the Sacco-Vanzetti case, which damaged American prestige abroad. In recent years some damaged footage was discovered and restored. Historian Robert D'Attilio showed the footage and commented on the heavy police presence at the start of the march from downtown Boston. An attempt to re-route the march from certain streets failed.

David Rothauser, who produced a film entitled the "The Diary of Sacco and Vanzetti," then read two letters from Nicola Sacco during his imprisonment, including a final letter to his son, Dante. He also read a celebrated statement by Bartolomeo Vanzetti from the last days of his life in which he calls the ordeal of his and Sacco's suffering a "triumph" for educating society on the need for greater justice. The writings of Sacco and Vanzetti remain in publication in a Penguin paperback.

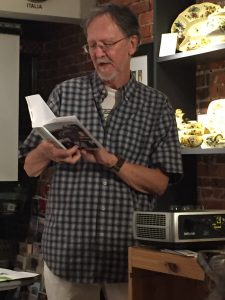

I spoke on, and read a few brief excerpts from, "Suosso's Lane," my novel based on Vanzetti's life in Plymouth, Mass., and the relationship between his times and our own. Here's an excerpt from my talk:

But the world does not end in 1927, with the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti. History in America, as everywhere else, goes on.

In my novel "Suosso's Lane," the details of the case are seen and discussed from perspective in the year 2000. We are in a new millennium when a young couple moves into a certain house on Suosso's Lane because the rent is manageable and the husband has his first real college teaching job close by. My characters discover that North Plymouth still has some of the characteristics of its working-class immigrant origins -- more affordable housing there than in most regional communities, more working class families and working poor. My young academic (I name him Mill Becker), a history teacher who has yet to find his true subject, learns to his surprise that a key figure in an internationally famous case in which the bigotry and the shortcomings of American justice scandalized the world, lived in apple-pie, Thanksgiving story, squeaky-WASP Plymouth at the time of his arrest.

Mill's interest is piqued. He looks for people to talk to. He looks into the historical conditions that produced the infamously flawed and prejudiced trial that convicted two men of murder without substantive evidence, but because of their political beliefs, the national mood of fear of radical violence or Communist revolution, and because of a widely held prejudice of the time against people of their national origin. To get an idea of how 'typical' native-born American regarded them, for 'Italians' substitute Muslims, Mexican criminals, or 'illegals' in today's partisan political discourse. In the course of his research Mill also discovers the existence of pre-World War I America, a time in history when lectures on free love by the anarchist Emma Goldman were widely attended throughout America, when almost a million votes were cast for the Prairie Socialist Eugene V. Debs (in the presidential election of 1912), when the ruling class faced challenges from both left and center, from the anarchist guru Luigi Galleani and the anti-monopolist Theodore Roosevelt; when an array of left-wing movements and theories (and some right-wing ones) challenged the status quo, ranging from the Farmer-Worker parties in Minnesota and other states, to the racist Jim Crow movement of the former Confederacy. Also a time when other major issues and causes were passionately debated: women's suffrage. Temperance, an idea that addressed the symptoms of poverty but not the cause. (Think "drugs," and substitute 'the evil of drink.') It led to Prohibition.

It's a period of American life that that our own times appear to have largely forgotten, a time of relatively unfettered radical agitation that came to an end with the Red Scare.

No comments:

Post a Comment